Set

Presented by Dancehouse and Sarah Aiken

Sarah Aiken: Concept, performance and choreography, set/object design and construction

Daniel Arnott: Creative collaborator, sound design, AV and set design

Amelia Lever-Davidson: Lighting design and operation

Matthew Adey/House of Vnholy: Object design and construction

With Ella Meehan, Claire Leske, Lilian Steiner and Kathleen Campone.

Duration: 50 minutes

This project was generously supported by Dancehouse through their Housemate Performance Residency and by the Victorian Government through Creative Victoria.

Additional seasons as short work : Piece for Small Spaces (Lucy Guerin Inc.) 2014, Expressions Dance Company Solo Festival of Dance QPAC 2015, Dancemakers Toronto 2018

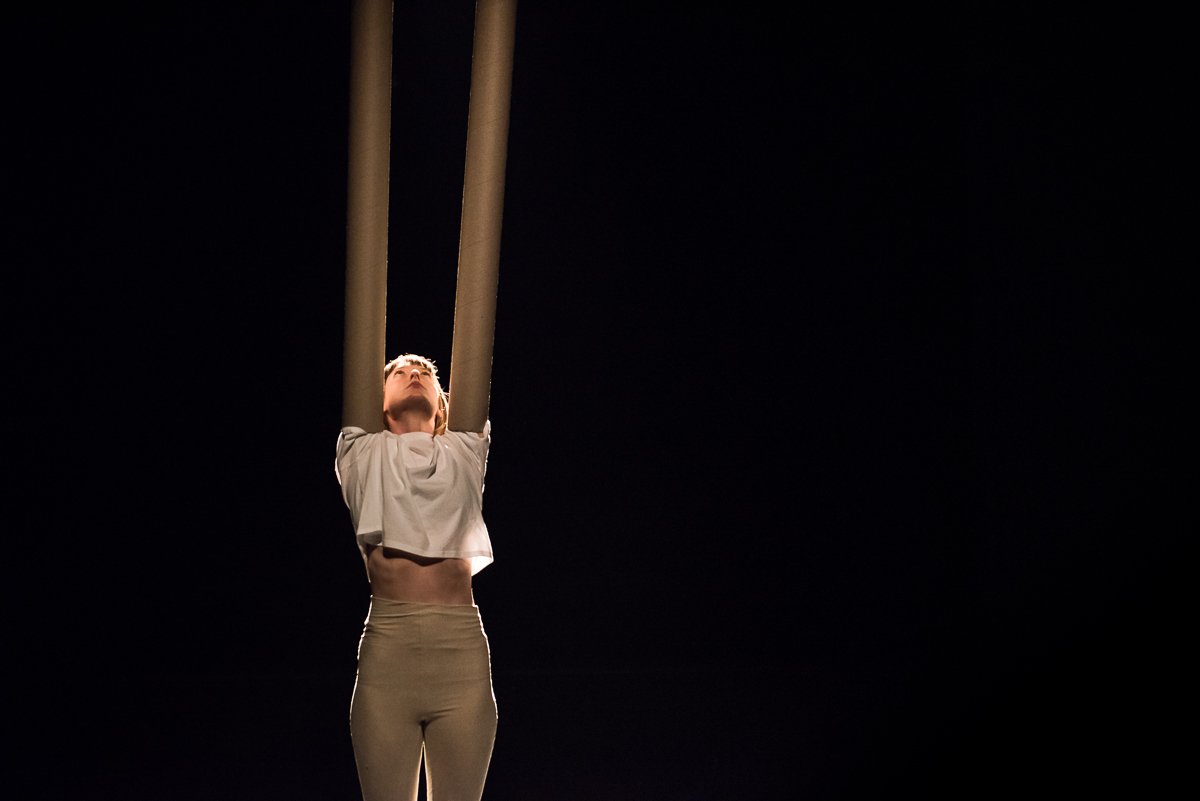

Moving from the mundane to the spectacular, from the sublime to the ridiculous, SET distorts and manipulates bodies and objects to playfully reimagine perspective, scale and perception. Choreographed and performed by Dancehouse Housemate/artist in residence Sarah Aiken, SET is a dance for one body and several objects; a work straddling the absurd and representational, repeatedly shifting how we value simple objects and the body interacting with them, ultimately revealing the human in all that is represented.

Images: Gregory Lorenzutti

Reviews

"Arnott and Aiken are possibly the first team I have ever experienced who fully understand all the qualities of space. How it changes, how it undulates, how scale can shift and focus can be manipulated. They demonstrate how our senses are engaged both consciously and unconsciously through lighting and sound. They mess with our cognisance by playing with the manipulation of projection techniques and live performance. Set is a journey into understanding how we can be manipulated. It looks at how with the tiniest shift, everything can change" Samsara Dunston, Planet Arts Melb

Sarah Aiken’s “SET,” (2015) celebrate the utilitarian object, redefining its role and how we regard it. After all, ‘readymade’ (tout-fait) is a homophone for ‘to-make’ (tu fait); it is up to you to make of it what you will" Gracia Haby, Fjord review

"Her body becomes a sculptural object...beautifully wrought, an exercise in simplicity and innovation" The dance life of objects. Varia Karipoff. RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. 25

"Singular and multiple at the same time, moving through tenses" Michelle Mantsio. Stamm

"Diminishing the boundaries between set and performer" Chloe Smethurst, The Age.

"[SET is]about the inherent qualities of everyday objects but also the qualities and values we project on to them … they represent a lot more than their physical form’. Because SET is about challenging perceptions, Aiken is required to treat herself ‘as both object and subject’" Maggie Journal of Live Arts

"Aiken's work is a delight with its own personality, fully engaged with wit and visual verbal wordplay" Liza Dezfouli, Australian Stage

Full texts

Australian Stage

Liza Dezfouli

Friday, 24 July 2015 20:01

Set | Sarah Aiken

Sarah Aiken is a Dancehouse Housemate/artist in residence. Her work Set is whimsical and self-effacing, starting off relatively simply with Aiken curling herself, rotating on the floor while a blue plastic tent, a geometrically shaped object rotates in a foreshadowing of later elements of the dance.

A cloth arm with a hand forms a carpet on the floor – a welcoming carpet, path, a moonlight path, a helping hand? Using her body, Aiken balances long tubes against a wall, creating a tension of wondering in the audience – will the tubes fall? The cardboard tubes become extensions of the dancer’s limbs, she’s on her back waving them, like a giant insect. The tubes remind you of spot lights at movie premieres, fronds, the hands of a clock, semaphore flags, mechanical things.

Set moves into an increasingly witty and structured engagement with space and objects. Surprises happen when the dancer, providing a retro-active appreciation of her earlier feats of balance, tips up the tubes to release various items hidden inside them – a running shoe, a rubber dinosaur, a faceted glass paperweight, shells, false teeth and a coffee mug. These come into play as tiny things once a camera is employed to rearrange and deconstruct dimensions; we see them on a screen formed by the cloth arm, and the dancer becomes another object in the set. Parameters, weights and the meanings of things are all distorted – ordinary things become monstrous and mysterious – along with their relationship of the human body. Aiken poses against the ‘set’; initially we are invited to see the dancer as self-conscious and aware of her beauty, while she becomes a sprite, diminutive against a giant shoe and mug. Aiken allows the extensiveness of the effect of her becoming Lilliputian to be enjoyed as she increasingly uncovers the playful underpinnings of the work.

Three other dancers join Aiken in a ‘tubular migration’ to Nick Cave’s song Into my Arms, then audience members join in, literally moving ‘into each other’s arms’, joined at the shoulders by the tubes. A disco ball and potted plants provide a hint of a show time finale.

Set is a gently amusing piece. It’s playful, enjoying its visual puns and the juxtaposition of everyone’s favourite love song against a literal interpretation of the words, a shift from the earlier dominant droning music.

At first Set comes across as a work following trends; we’ve seen quite a few dances over the recent years using video and objects; Set is in the same vein as the choreographies of Atlanta Eke; however Aiken's work is a delight with its own personality, fully engaged with wit and visual verbal wordplay.

Set: Prestidigitation or so I like to imagine

Michelle Mantsio

Stamm August 2015

An effective architectural plan can realise through floor plans and elevations a solid three-dimensional building. We imagine it forming in our minds and in that moment qualities of abstraction occur. Once initiated in this trickery, we can carry it with us anywhere. Might we become trained in our capacity to imagine more, to handle more?

I like to imagine that Sarah Aiken’s Set, performed at Dancehouse, built space using the tropes of Romanticism, through the use of her newly extended limbs, vignettes and spatial illusions. The performance consisted of Aiken attaching tubular limbs to her arms and legs, which not only moved with her, but also became set props within the space. In Romanticism, the introduction of the the pointe shoe as appendage led to the lifting of the length of tutus to reveal the foot, as well as an emerging focus on female dancers and the extended line of the body. In Set, Aiken extended the length and scale of the exterior limbs to new dimensions. Through these appendages the body was scaled up to set proportions, which then threw out the scale of the theatre. Too big? Too small? Not sure? Look again.

I like to imagine these extended limbs were a bit like her hair: blunt, sharp bangs. When coupled with her red lipstick, and her languid timing as she moved into various vignettes, she threw out a kind of 1980’s Helmut Newton posturing. Strong sharp women who maybe wear blunt sharp shoulder pads for fun (or maybe a little power). Initially I found the vignettes a little trite, but actually they worked well as accents to lead us through the performance. Through their laconic timing in the piece they created a pause, drawing attention to the design and conceptual propositions of the work.

I like to imagine the spatial illusions or trickery came through with the construction of three spaces existing simultaneously. It felt like stepping into a Frances Stark work, whilst simultaneously still being in the audience, and so challenged my sense of embodiment, but in the best way possible. Singular and multiple at the same time, moving through tenses. Could I be stretched? Could I handle more? The prestidigitation of Aiken walking between these objects, was constructed with enough material clunkiness and glitching that it revealed the illusion and effectively honed our focus between real and perception.

At times it was dense (maybe a little heavy), but like Ntone Edjabe says in the House of Truth, “Good. Sometimes this is better.” Or so I like to imagine.

Samsara Dunston

Planet Arts Melb

Set - Dance Review

Friday, July 24, 2015 - 15:29 http://www.planetartsmelb.com/118746

5 Stars

When I was in Dancehouse this week I saw a sign which identified it as a centre for moving art. I was there to see Sarah Aiken’s new work, Set, and even before the performance began, this idea had me thinking about Dancehouse and it’s place in Melbourne’s arts landscape.

Having seen Set, I feel like I have an understanding of what that statement means. Just as moving image is more than just film, moving art is more than just dance. For the first time in a very long time, with Set I saw something that truly seems like a new live interaction on stage.

In Set, Aiken engages in an exploratory interaction between space and the objects and aspects of that space. Rather than this being a dialogue about dance, this work places the dancer as one of a range of elements working within and affecting the room.

What is fascinating is that rather than prioritising the animate (herself), instead she engages the inanimate. I don’t know where the line is drawn between what happens in Set and puppetry, and I wouldn’t call anything about Set puppetry.

I think it is because whilst the inanimate objects, which include props and lighting and sound, are activated and in constant wax and wane, they are not anthropomorphised. Nothing in the room – including the performer – are given personality or human qualities (except towards the end when Aiken smiles and the audience are physically engaged).

Arnott and Aiken are possibly the first team I have ever experienced who fully understand all the qualities of space. How it changes, how it undulates, how scale can shift and focus can be manipulated.

They demonstrate how our senses are engaged both consciously and unconsciously through lighting and sound. They mess with our cognisance by playing with the manipulation of projection techniques and live performance.

Set is a journey into understanding how we can be manipulated. It looks at how with the tiniest shift, everything can change. The conversation begins with a question of ownership of the space as a huge felt hand covers half the audience seating, leaving the audience to fill only one side of the space. Slowly this shifts even as people are still entering. The performance is happening from the moment we enter the space.

Much of the dialogue about this piece has centred around the work Aiken does with long cardboard rolls – similar to those used to hold bolts of cloth. This movement – and the work really is built in movements – is mesmerising and Aiken’s strength and control and perfect form are really highlighted here. Everything relies on her maintenance of perfect line in order not only to achieve the visual aesthetic, but also the conceptual intent. To have even a moment of imperfection would change everything.

Again, I found myself thinking of another discipline – circus. Much of this first movement with the rolls required so much from Aiken that every time a sequence was completed I wanted to cheer and applaud. Of course I couldn’t because this is ‘dance’ and with ‘dance’ – especially ‘modern dance’ – you don’t do that until the very end.

Even when I chuckled people looked at me as if I had sinned – until much later when suddenly everyone else in the room realised that there was humour in the work. Given that in the program notes it says ‘Sarah…[aims] to create poignancy through absurdity’ I would have thought there would be a greater relaxation about the audience.

Aiken dances a beautiful architecture in this first movement of the work. It is delicate, and it moves at a mesmerising pace as each point of discovery about the relationship between the moving objects (herself and the rolls) and the space and lighting was revealed. Working in the corner, the first direct metaphor was revealed – balance. In many ways Set is all about balance. Physical balance, spatial balance, and conceptual balance.

The second movement focuses on scale and cognition, with Aiken working live in the space with a live projection of herself. You may think you have seen this sort of thing before but trust me, this is new and revealing.

In the final movement Aiken re-engages with humanity – her own, her assistants, and also the audience. No words are ever spoken throughout this performance, but when it comes time to interact, the chosen ones easily figure out what they are being asked to do. Again, this section is about balance – the balance between people.

In many respects Set is a Utopian work and even provides a ‘happy ending’ in a wonderfully absurd conclusion. It definitely is a thought provoking and most beautiful piece of moving art.

On a purely technical level, I recommend every performance maker and designer (of all disciplines) come to see this performance. Even the best amongst us will likely come away with a new understanding of the tools we work with - and their balance...

Fjord Review

“SET” Sarah Aiken

Dancehouse, Melbourne, Australia, July 24, 2015

A single bicycle wheel upturned and mounted upon a stool (Bicycle Wheel, 1951, third version, after lost original of 1913). A snow shovel (In Advance of the Broken Arm, 1964, fourth version, after lost original of 1915). A painted window (Fresh Window, 1920). When Marcel Duchamp placed a mass produced ‘readymade’ before us and disrupted how we thought about and interpreted art, the “ordinary object [was] elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.”1

The objects were important not because of what they were, but because they were selected by the artist. Removed from their ordinary function and thereby stripped of their usage, the object became art. With the integral addition of the onlooker witnessing the work and responding to it, the ‘readymade’ “created a new thought for [the particular] object.”2 We, the spectators, in accepting the role of transference through the act of looking, choose what we see in Duchamp’s ‘readymades’. Under our gaze, objects can take on entirely new and obscure meanings.3

To my mind, following this train of thought, both Reckless Sleepers with Nat Cursio’s performance of “A String Section” (2012) and Sarah Aiken’s “SET,” (2015) celebrate the utilitarian object, redefining its role and how we regard it. After all, ‘readymade’ (tout-fait) is a homophone for ‘to-make’ (tu fait); it is up to you to make of it what you will.

A free, one-night-only performance of Leen Dewilde’s “A String Section,” as part of a seemingly perfect exchange between the Belgium/UK based company, Reckless Sleepers, and current Coopers Malthouse resident, Nat Cursio Co., released the humble handsaw from its place in the tool shed. Coupled with a timber chair to chew through, it became a musical instrument for 50 minutes in the Bagging Room of the Malthouse Theatre. A musical instrument wielded by Cursio, Dewilde, Alice Dixon, Caroline Meaden, and Chimene Steele-Prior, who proceeded to reduce the functional to sawdust. As befits an orchestral quintet, each performer wore a black dress and neat heels. And in their hands, each held their bow, an orange-handled saw. Their instrument: a wooden chair (varying quality and style). Their invitation extended: “watch [an] object have its history changed in front of you.”4 Embracing the idea of the ‘readymade’, I was free to redefine the object’s role and thereby ascribe my own meaning.

From my external world, I brought to ‘the creative act’, my own sensitivity and humour. And as with Cursio’s “Tiny Slopes” work-in-progress teaser, seen earlier in the year as part of Dance Massive 2015, I saw my own self in the actions of the performers as opposed to laughing at them and their attempts to saw a chair leg whilst remaining seated or crouched on the chair. I wondered if they were ever tempted to pick up their chairs and break the limbs through force as opposed to the slow snaggle-toothed slog of back and forth with a handsaw. I imagined what it would be like to be a part of this work:

Imagine sitting on a chair. Lean forward, keeping your feet on the ground, if you wish, and commence sawing with your preferred hand at one of the two front legs. You may wish to hop off the chair and saw, or to place the chair on a workbench, but this is not permitted. You must saw the chair leg whilst balanced on the chair. You will need to move your own body weight in order to do this. You will need to contort your form. You may extend a leg outward and hold it in the air for balance like a prehensile tail. You will probably find this awkward. And this is only the first step. The teeth of your saw may catch. This is to be expected. Work through this. Keep going. In 50 minutes, your task is to reduce the chair to pieces and sawdust. In this period, you will have turned the functional into something useless. You will have transformed an object into nothingness. For this, you may have a blister to show for your labour. You may also have a sweaty brow. Your black orchestra pit attire will be covered in fine powder. You will have reduced a beautiful timber chair to crumbs, but given it a great finale. The sound your saw made as you worked, your music, and the struggle of the task, reflective of the artistic process. In a grandiose moment, you may have reinterpreted the words of Théophile Gautier as you thought: “There is nothing really beautiful save what is of no possible use.” In the end, it all ends up scrap.

I responded to the determination and conviction of the performers as I read my own frustrations in their labour. I admired their balance on their wonky-legged rafts, and devoured their deadpan humour. This work, to me, was about strength in all its guises: strength to continue, to pursue your own goals, a recognition of the hard slog of getting things done. Watching the performers adapt to their seats as they became increasingly unsteady, to me, was a picture of the creative act in all its warty (or is that dusty?) glory. But if the mundane and the functional can became a musical instrument, so too can a hardship become a victory. All too often it is from this standing that new ideas can be explored. Shifting positions throws up not just challenges, but new perceptions. And this idea of how things look and how things are was also woven into Dancehouse Housemate/artist in residence Aiken’s new work, “SET,” which looked to “distort and manipulate bodies and objects to playfully reimagine perspective.”5

Comprised of three vignettes, as with “A String Section,” it was shown that you could lose your footing and regain it. A dancer can alter their proportions in such a way to transform from a gangly giraffe unsure of where their limbs end (when standing upright) to a broken timepiece (when rotating clockwise on the floor) with the aid of four long cardboard cylinders. With all four limbs encased in tubes, lying on her back, legs and arms extended upwards, Aiken shape-shifted and became a piece of unworldly and unyielding seaweed. But the greatest transformation took place in the second vignette when Aiken made herself appear, through overlaid projections, no taller than a black coffee mug.

Projected onto a large white piece of fabric cut out in the shape of a giant glove, which had been slowly winched into place, what we see and what we know was tested. The projected image appeared to be a live playback of the stage to the left of the giant glove. So far, so surreal; both projected image and stage appeared in cahoots. There, the black coffee mug, and over there, the single white sneaker. In keeping with the monochrome, over there, a grey plastic elephant. Atop this accepted visual, a second appeared, that of a shrunken Aiken wandering through the assorted miscellanea. A digital collage, Aiken was rendered the size of the forms she negotiated. Upon the makeshift screen, how I read scale had been cleverly (though not seamlessly) altered. The toy elephant, on screen, had assumed actual size. My eyes took in the visual conjurer’s trick and flitted back and forth from the altered reality of the screen to the ‘real’ scene. Several yoga-like poses undertaken in the far left of the room on the lip of an existing stage seemed unremarkable, but looking back at the screen this was actually the exact area inside the black mug. It gave the impression of Aiken as a genie in a bottle, a performer in a coffee mug undertaking their morning asanas. Distorting scale and toying with my perception, this simple illusion was one of the strengths of the piece.

Given the opportunity to complete both pieces through my own willingness to engage, the transference between performer/work and audience/spectator was completed. Through an unspoken dialogue, I, like those seated around me, became a transfixed part of “A String Section.” Through audience participation, we became, quite literally, the missing slow-shuffling link in “SET,” as Nick Cave crooned “Into My Arms” and the disco ball twinkled. In the middle of winter, armed with saws, chairs, and cardboard tubes, everything was related and connected, as we attempted to put art back “in the service of the mind.”6 Since then, I have been left with a hankering to saw at the very foundations I sit on whilst my limbs are encased in cardboard cylinders; I couldn’t have asked for more.

Maggie Journal of Live Art.

Mary Ntalianis

Sarah Aiken's latest work SET is currently showing at Dancehouse as part of their Housemate Performance Program. A dancer, teacher and choreographer, Aiken graduated in 2009 with a Bachelor of Dance from the Victorian College of the Arts. She is full of praise for the supportive atmosphere Dancehouse provides for young dancers and choreographers. ‘A lot of people have a history working with or at Dancehouse because they provide studio space and so many workshops … there’s always stuff happening here’.

For Aiken dance has a special place within the performing arts because, in a dance performance ‘both the audience's and the performers' bodies are in the room together, undergoing a special connection that happens outside literal experience … communicating in a way that isn’t linear or literal in shared space’. SET aims to challenge our perception of scale and space by distorting and manipulating both objects and bodies to find the connection between the sublime and the mundane. Asked whether there is any audience participation in SET, Aiken laughs, admitting that the impact of most of her works depend on an 'exchange between the performer and the audience … the performance wouldn’t exist without them [the audience]'.

SET was originally a short work created for Lucy Guerin’s Pieces for Small Spaces in 2013. Pieces for Small Spaces is Lucy Guerin Inc's annual program to support the work of young choreographers and those working outside company structures. Five choreographers are invited to make a 5 to 10 minute dance work with the aim of developing choreographic process and finding a distinct voice for their ideas. The experience left Aiken with the desire to create a longer work 'about the inherent qualities of everyday objects but also the qualities and values we project on to them … they represent a lot more than their physical form’. Because SET is about challenging perceptions, Aiken is required to treat herself ‘as both object and subject’. Humour and absurdity are also present in Aiken's work, ‘I’m very interested in the place where you’re not quite sure, because I’m loading value onto such mundane things and treating an object like it has it’s own subjectivity, the comedy comes out of the absurdity of it all’.

Despite being unsure about future projects, Aiken plans to keep performing and choreographing, saying that she feels like there is so much she has yet to explore. ‘Each work is an opening into all the things you have yet to do, everything that I’m doing with this work is following a trajectory; it couldn’t have existed without the work before it, and the work after it will not be able to exist without [SET]’.

Set review: Sarah Aiken's cardboard choreography on a roll

Chloe Smethurst. The Age

July 23, 2015

Diminishing the boundaries between set and performer, Sarah Aiken's latest creation is as much a choreography of objects as a dance. Using large cardboard tubes as well as a host of other props, Aiken develops several lines of thought.

In one scene, she slowly propels herself around in circles while seated on the floor. Her movement is mirrored by a large, dark, angular prop in the background. Amelia Lever-Davidson's lighting catches the planes and surfaces of both body and constructed shape as they mesmerically spin.

Suddenly, four long tubes are released. As they roll towards Aiken, seemingly of their own volition, the lines between object and performer are further blurred. Lying on her back with one tube on each upraised limb, Aiken gently sways, creating a kind of kinetic sculpture with her four elegant poles.

Later, Aiken constructs an imaginary world, instantly rewarded video-game style by Daniel Arnott's synthesised sound and Lever-Davidson's softly glowing lights for every item that she finds or manoeuvres. A cleverly manipulated projection captures Aiken's movement and digitally shrinks her to the height of the coffee cup on stage, heightening the sense of unreality.

In the final scene, Aiken is joined onstage by other women with tubular arm extensions, who form a circle and entice audience members to join their quasi-spiritual human meccano set. Thankfully, Aiken retains her sense of humour and finishes with a recording of Nick Cave's Into My Arms, slow dancing with an audience member under a disco ball.